On October 13, 2020, 15 newly elected members of the 2021 U.N. Human Rights Council were announced, including China, Russia, and Pakistan. These states hold regimes that regularly violate human rights protections and have evaded accountability for decades, raising concerns around their membership.

Figure 1. Slate for the 2021 HRC cycle: only the Asia-Pacific States had an active competition, leaving Saudi Arabia behind. (UN, 2020)

What is the Human Rights Council?

Formed in 1945 to advance the interests of international peace and security, the United Nations currently holds 193 members and is constructed of six major organs and many subordinate groups. The Human Rights Council, or the HRC, works to pass recommendations on international “situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations”

(UN, 2020). States are elected for three-year terms and may hold two consecutive terms. The HRC’s method of regional elections means that only the Asia-Pacific region had a competitive slate, as seen in Figure 1- the rest are virtually assured seats.

The announcement of Russia, China, and Pakistan joining the Council was both shocking and anticipated, as all countries have been elected before, but continue to be among the top human rights offenders. Currently, 51% of the HRC members fail to meet the standards of a free democracy, and this new round of selections will push that number to 60% (Neuer, 2020).

The American Vacuum: A Consistent Call for Reform

To its advocates, the HRC is a place for states to consider human rights issues on the international stage. To its critics, it is a powerless organization that works under the watch of authoritarian power. The United States, although consistently demanding reforms over the past four decades, moved to the latter extreme in 2018 by removing themselves altogether. Nikki Haley, the Ambassador to the U.N. claimed that the council “ceases to be worthy of its name”, and that it in fact “damages the cause of human rights”

(Ward, 2020). President George Bush previously abstained from membership for similar reasons during both of his terms. Membership under the Obama administration was important symbolic support for European nations, but brought unsatisfactory results, with Rep. Eliot Engel, the ranking Democratic member on the House Committee on Foreign Affairs commenting that “the UN Human Rights Council has always been a problem”

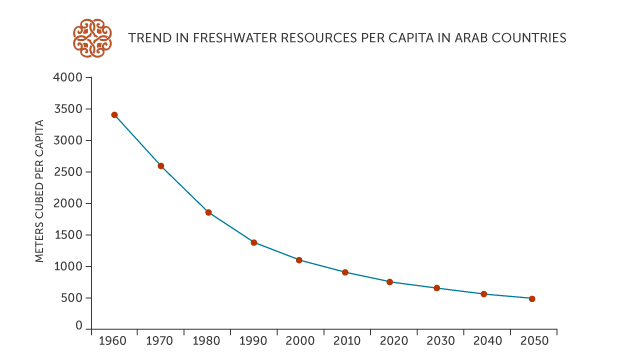

(Ward, 2020). Figure 2. Comparing the scores of China, Russia, and Pakistan with their democratic fellow councilmember the United Kingdom. Original graphic with information collected from the Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index (2019).

A Long History of Human Rights Abuses

Analyzed by the Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index, the scores of these three members in comparison to the United Kingdom show a disturbing dissonance between the behaviors of council members and their membership in the HRC.

Pakistan

Ranked 140th out of 162 nations is Pakistan, with abysmal scores in the area of human rights that it has been elected to protect

(Cato Institute, 2019). Freedom House’s Global Freedom Report generally concurs with this analysis, giving it a 38/100, and describing it as “Partly Free”

(Freedom House, 2019). Authoritarian practices including voter intimidation and prescribed attacks on the media, religious minorities, women, and transgender individuals are at extremely high rates, with the “honor killings” of young females garnering recent international attention

(Human Rights Watch, 2019). The Global Barometer of Gay Rights reveals the extent of anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice, allocating a mere 7% and a failing “grade” to Pakistan

(GBGR, 2017).

China

Barely surpassing Pakistan’s ranking, China scores a 124/162 on the

Human Freedom Index (Figure 2), and an egregiously low 10/100 “Not Free” ranking on Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index

(Freedom House, 2019). Ethnic violence has reached new extremes, causing China to be one of only 11 countries cited for ethnic cleansing

(Freedom House, 2019). Draconian bans on religious activities, the prosecution of labor rights and human rights advocates, and the scrutiny of non-governmental organizations, have been steadily increasing. Recently, the Xijiang detainment camps, in which Uyghur Muslims are forcibly kept, tortured, indoctrinated, sexually abused, and killed, have caused a major public outcry, which has been largely ignored in Beijing

(Gan et al., 2020).

Russia

Internationally recognized as a corrupt nation, Russia scores a 114/162 on the

Human Freedom Index (Figure 2), and a 20/100 “Not Free” ranking on the Global Freedom Index

(Freedom House, 2019). Russia has recently been most recently cited for violence against the media and political opposition groups. The murder of activist Yelena Girgoryeva and the attempted assassination of Alexei Navalny are two in a string of disturbing events targeting Putin’s opponents. Similarly to Pakistan, elections are marred with heavy intimidation, and military officials regularly torture and kill persons in custody. Of even more concern are the deliberate attacks on non-governmental organizations and human rights advocates, fundamentally clashing with their own role as human rights defenders.

Globalization and its Complications

An obvious commonality of these states is their unofficial practice of authoritarian government, promoting coercion-based oppressive power behind a veil of democracy that often breaches the protection of human rights (O’Neil). The UN General Assembly’s Resolution 60/251, responsible for the creation of the Human Rights Council states that elections should “take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights,” a notion that seems to suggest basic requirements

(UN, 2020). The fundamental dissonance between the goals of this council and its representation has highlighted the need for reforms, including the promotion of competitive regional slates, and the disqualification of rule-breaking nations.

However, any movement from the current deadlock is not likely, as Western powers are bound to these three nations by a web of economic interests, and the true enforcement capabilities of the United Nations are limited. Peggy Hicks, the global advocacy director at Human Rights Watch notes that these countries are “powerful states that exercise their power in a way to influence others at the council, as well as make it very hard to engage on issues that they don’t want reviewed”

(Yu, 2013). Complicated globalized loans and investments give nations de facto impunity, advancing a vision of a world without accountability.

A Call for Reform

As an international body formed with the intention of maintaining basic standards of peace and protection, the clash between ideology and reality is palpable in the Human Rights Council and begs for a solution. Although a simple reform of standardized qualifications and competitive elections may seem obvious to Western powers, the grip of globalized interdependence makes movement, at least for now, wholly improbable.

References

Main Articles:

Ward, A. (2020, October 14). Russia and China will join the UN Human Rights Council. The US should too. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.vox.com/21515856/china-russia-un-human-rights-council-usa-trump

Yu, A. (2013, November 13). Does China Deserve A Seat On The U.N. Human Rights Council? Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2013/11/12/244853036/does-china-deserve-a-seat-on-the-u-n-human-rights-council

F&M Global Barometers. (2017). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.fandmglobalbarometers.org/

Gan, N., Westcott, B., Griffiths, J. (2020, June 19). What's been happening in Xinjiang, home to 11 million Uyghurs? Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/19/asia/xinjiang-explainer-intl-hnk-scli/index.html

Global Freedom Scores. (2019). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

Human Freedom Index. (2020, September 10). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cato.org/human-freedom-index-new

Nichols, M. (2020, October 13). China, Russia elected to U.N. rights council; Saudi Arabia fails. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-rights-idUSKBN26Y2YE

Okic, E. (2017, March 1). Human Rights Council- 34th Session [Digital image]. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.universal-rights.org/blog/relationship-human-rights-council-third-committee-ga-measuring-coherence/

O'Neil, P. H. (2018). States. In Essentials of Comparative Politics (pp. 30-61). New York, New York: W. W. Norton.

Pakistan 2019 Human Rights Report. (2019). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PAKISTAN-2019-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf

UN: Deny Rights Council Seats to Major Violators. (2020, October 22). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/08/un-deny-rights-council-seats-major-violators

United Nations, main body, main organs, General Assembly. (2020). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.un.org/en/ga/75/meetings/elections/hrc.shtml