The once respected freedom fighter President Robert Mugabe did it in 2002 to Zimbabwe’s opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, now Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda is doing it to his main challenger, Colonel (retired) Dr. Kizza Besigye. The arrest of Besigye in Kampala on Monday on questionable charges of treason and rape puts almost 20 years of progress and stability in Uganda under question. Besigye had just returned to Uganda from exile in South Africa in preparation for the March 2006 presidential elections.

What makes this latest African spectacle such a tragedy is that Uganda seemed to be a potential African success story. Uganda was once synonymous with violence, chaos and Idi Amin Dada’s predilections for human flesh. But since 1986 when Museveni and his rag-tag band of guerrilla fighters took over Kampala, there was hope. Museveni promised to bring political stability, economic growth, and good political leadership to Uganda. And he did for many years.

He introduced grassroots participation through Local Councils and a “no-party” political system. Past instability in Uganda was linked to politicized ethnicity argued Museveni, so if Ugandans could focus on the individual merits of candidates rather than their political party or ethnic, religious or regional affiliation, Ugandans might be able to focus on their similarities rather than their differences. Ugandans, fearful of a return to chaos, agreed to give it a try.

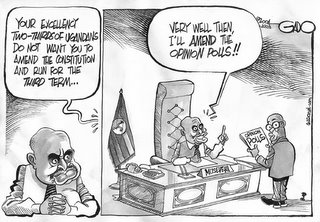

In June 2005 Ugandans voted in a referendum to adopt a multiparty political system rather than retain the no-party political system of government they had for the past 19 years. Museveni was able to change the constitution to allow him to run for a third term in the March 2006 Presidential elections.

While Western governments and the donor community were uneasy about Museveni’s questionable dedication to multi-party democracy Museveni’s economic successes and embrace of macro-economic reform helped assuage some of those concerns. Uganda under Museveni had one of the fastest growing economies in Sub-Saharan Africa. It had opened up its markets to international investment, and was willing to implement stringent structural adjustment programs. Museveni became a poster child of economic reform, receiving millions of dollars in foreign aid, and 100 percent debt relief from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the African Development Bank.

Museveni was viewed as a new breed of African leader – a visionary -- one of the African Renaissance leaders. He was intelligent, savvy, beyond corruption (although it was doubtful that those surrounding him were) and dedicated to his people.

Of course, not everything has been so encouraging in Uganda. The Ugandan army has been fighting a northern insurgency since 1986, currently led by Joseph Kony, the fanatical leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army. Uganda’s imagine was tarnished by its military involvement in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And, most disturbingly, Human Rights Watch, an internationally respected non-governmental organization, published a 76 page report documenting widespread torture of political opposition members in Uganda.

So, what happened? How did the “darling of the West” start sliding down the slippery slope of authoritarianism? Did power simply become too intoxicating? Museveni and his supporters became convinced that no one could run Uganda as well as he could. A familiar argument made by many former self-appointed “Presidents for life”. Museveni is not an anomaly: The number of African leaders that have peacefully stepped down from power can be counted on one hand: Jerry Rawlings in Ghana, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, Daniel Arap Moi in Kenya, and of course Nelson Mandela in South Africa.

Unless Museveni allows Besigye to run for President and lets the democratic process and rule of law determine who should be Uganda’s next president, Uganda may join the ranks of some of the current African trouble spots including, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Cote D’Ivoire, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

The international community must demand that Museveni uphold the rule of law in Uganda. Donors should cut off aid to the Museveni regime, and the African Union should strongly rebuke Museveni. But most importantly, Ugandans must peacefully demand justice and democracy. The world is watching, and hoping desperately for another African success story in a country that Sir Winston Churchill once called the “Pearl of Africa”.

By Susan Dicklitch